We were approached recently by a client who wanted to add a bookcase door under the enclosed stairway of their 1910’s Tudor Revival cottage. There was a substantial amount of inaccessible space underneath the stair after a closet had been walled off during a previous remodel. The build is still in progress, but I’m going over the finer points of the install here while the details are fresh with the intention of updating this post after drywall repair, paint, and a few other odds and ends after the holiday.

Preparing the Opening

To allow access from the entry wall where the bookcase door was intended to go, we had to do some fairly intensive demolition. There were load-bearing studs underneath the stair that were supporting the mid-stair landing and the subsequent string to the second story. We doubled up the trimmer studs on either side of the opening with new bottom plates with the point load bearing directly over floor joists. A double 2x6 header with a double hanger provided adequate load transfer to remove the studs in the way.

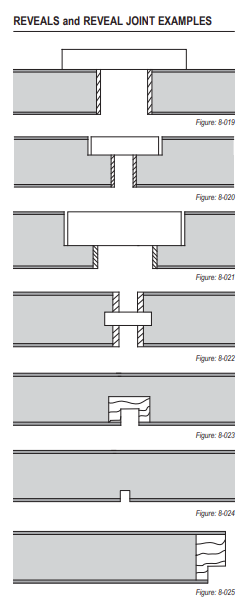

Now, we had a rough opening ready for a bookcase door, but there were still some obstacles. The clients wanted an out-swing door to maximize the already limited space inside the closet, and the door needed to clear a floor grate, the air intake for the furnace. For this reason, we opted for an inset double face-frame design which had a few major advantages:

Strength: With the cabinet and its hardware bearing on two 3/4” maple face frames, we virtually eliminated any risk of racking in the front

Function: by swinging out 2-1/4” over finished floor, we would miss the air intake entirely.

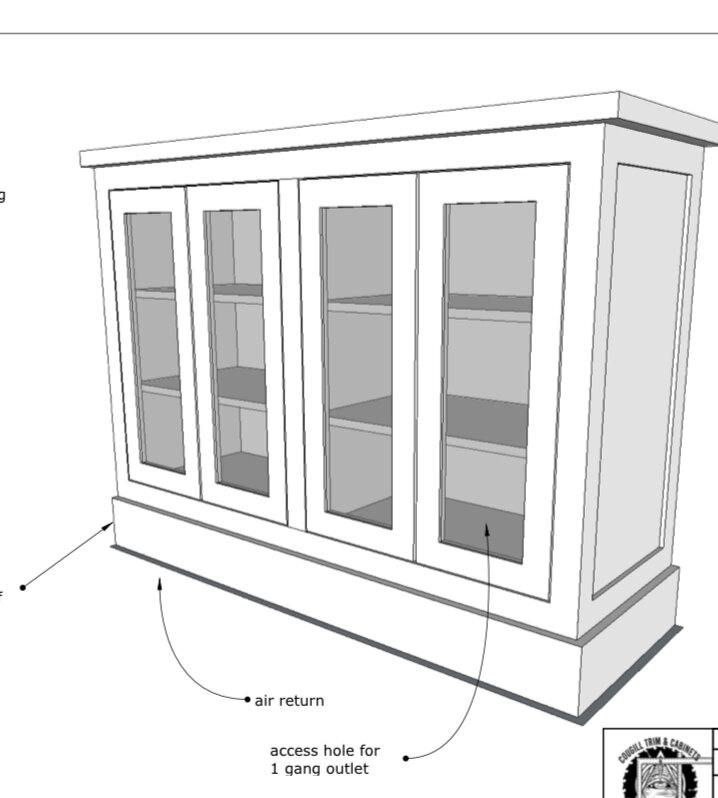

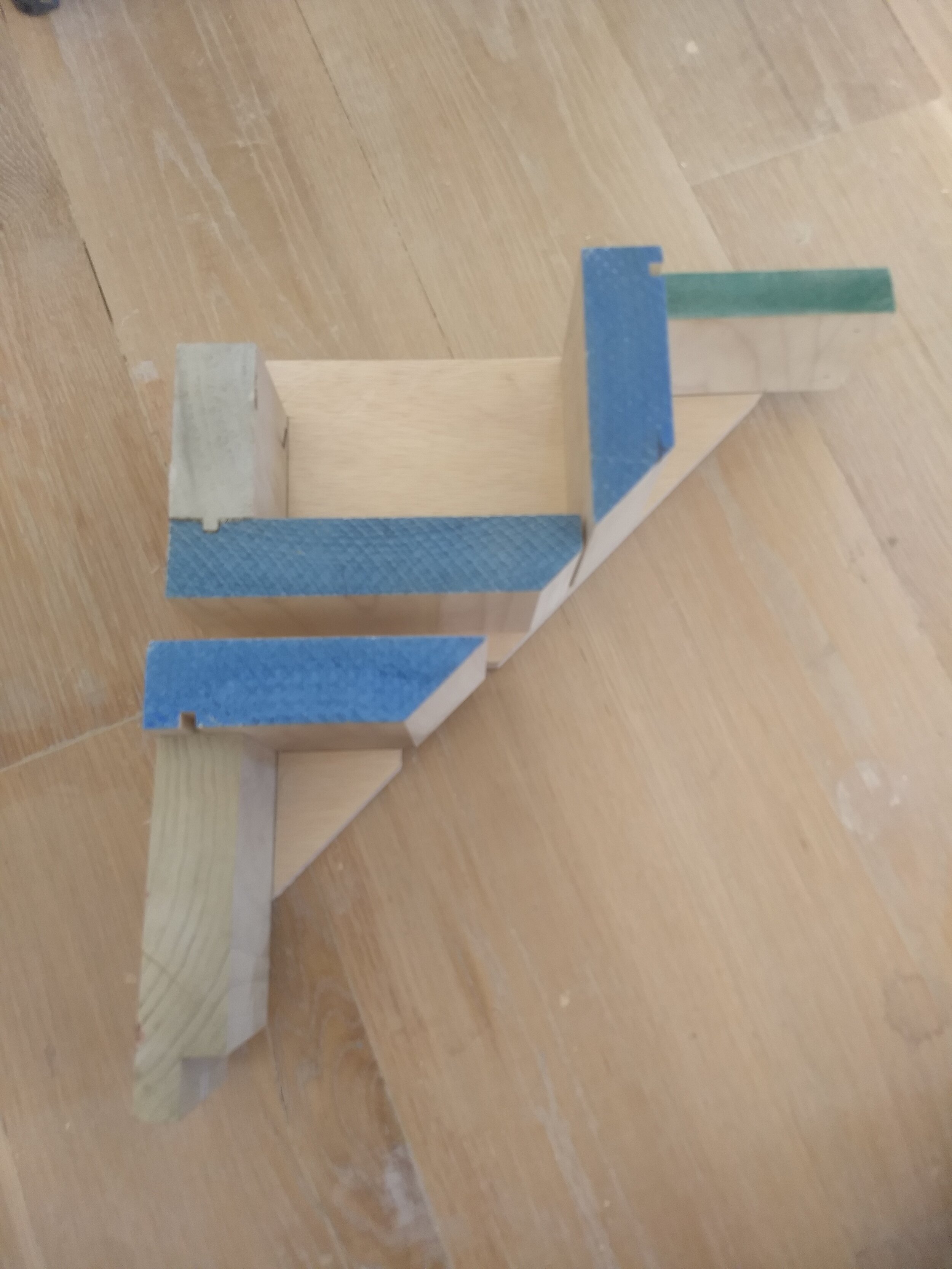

However, this did present a few additional challenges. Most pocket door kits are designed to mount directly to the floor or to hinge off of a 2x4 jamb using something like a Soss hinge. In this scenario, the wall was 3” thicker than the framing due to a prior remodel which added furring strips and drywall over the existing lath, horehair plaster, and original trim. There wasn’t room in the budget to rip it all out and start fresh, so we opted to keep the current wall depth and work around it. The best fix seemed to be adding 2”x2”x8” hardwood blocking to the back of the outer face frame. This created adequate bearing points for two heavy-duty pivot hinges. With this system, we could build the entire unit off-site and test/adjust hardware before enclosing the unit in a wall cavity. Work space in this home was tight already; building everything off-site was highly preferable.

The Finer Points of Bookcase Door Function

Racking

Many bookcase doors have fixed shelves because they provide additional support. This limits what the shelves can store though, so adjustable shelves are a better choice if possible. This does require a bit of planning though to keep the whole unit from sagging. A heavy duty face frame in hardwood glue and screwed ensures that the face of the unit won’t sag and distort over time. The back of the bookcase was rabbeted in, then glued and stapled. This provides additional resistance to racking and binding over time. Finally. the whole shelving unit was built from plywood to keep weight down to a minimum. Because of plywood’s high strength-to-weight ratio, the unit can hold more books without putting undue strain on the supporting structure.

Clearance

A bookcase door is a rectangular prism moving through a rectangle, so there has to be clearance on the strike side (the side opposite the hinges). This presents a few challenges with the design, since you’re hoping to maximize space, any wasted space should be minimized. When we face this same problem with swing doors in standard jambs, we bevel the door, usually about 3 degrees, to clear the jamb when swinging through the jamb. To accomplish this with bookcase doors, we oversize the face frame and undersize the bookcase so that there’s a gap on the strike side. In this case, the bookcase itself is 7-1/4” deep on a 3/4” face frame. That means I need the hypotenuse of the triangle formed by the jamb, carcass side, and pivot point to clear the jamb. I drew all this up in cad and pivoted it to see if it would work, then adjusted as needed. I’ve seen too many of these with awkward modifications to clear jambs and didn’t want to have to deal with that on-site.

Bearing

All of the hinge options out there for this are pushed to their limits swinging an over-loaded bookcase, so by managing the depth and using the heaviest-duty hardware available, you at least have a fighting chance. The obtain the same load rating in a Soss hinge as a pivot hinge, the cost would have doubled, not to mention the added labor of a complicated 2-step mortise required. I like InvisiDoor’s system that can be purchased through Custom Service Hardware.